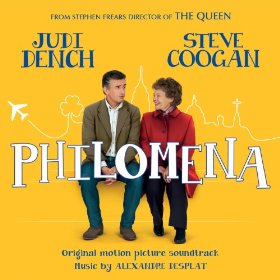

“Philomena” is based on a true story about an elderly Irish woman searching for the toddler son she gave up for adoption as an unwed teen living in a convent. Most of its pleasures come from the way it confounds expectations.

From its odd-couple partnering of the usually stately Judi Dench and acerbic jester Steve Coogan (also co-writer and producer) to its remarkable cliché-avoiding yet still-emotional conclusion, the movie defies pigeonholing. What appears to be a simple sob fest eventually reveals itself to be a multi-faceted affair: part buddy comedy built upon class distinctions, part road trip adventure, and even part intriguing mystery.

Some might be taken aback at first by Dench, still the grandest of all British dames at 78, as Philomena. The character is a middle-class commoner of modest tastes, complete with a matronly coif, a utilitarian wardrobe and an appetite for salad-bar croutons, romance fiction and those free chocolates left on hotel pillows.

We are more accustomed to Dench in such luminously regal performances as the widowed Queen Victoria in “Mrs. Brown,” a commanding Queen Elizabeth I in “Shakespeare in Love” and James Bond’s no-nonsense boss M. Don’t be fooled, however. This might be one of her most complex portraits: a seemingly average person with an unlikely reserve of strength.

Her Philomena would have every right to act the victim, considering the traumatic circumstances that caused her to be separated from her child, and the vow of silence about the matter that was forced upon her. Yet the actress slowly but surely reveals Philomena’s fortitude in the face of awful truths, her immense capacity for empathy, and her sharp insight into human behavior—along with a healthy frankness about sexuality despite the best efforts of the nuns who tried to brainwash her otherwise.

Dench’s usual brilliance is fully utilized by director Stephen Frears. He did well by his leading lady previously with “Mrs. Henderson Presents” and steered a dowdy Helen Mirren to an Oscar win in “The Queen” before indulging in more recent trifling fare as “Cheri” and “Tamara Drewe.” He is right back on track, however, nicely balancing the contemporary portions of Philomena’s journey with scathing flashback depictions of wrongdoing and deceit at the rural Roscrea facility back in the ’50s. The nuns there would snatch away toddlers born out of wedlock to young girls—who, like Philomena, toiled as indentured servants in return for shelter—and then sell them for a goodly sum to American families.

After establishing the circumstances surrounding the birth of Philomena’s son, Anthony—including a fairground interlude with a handsome lad who unknowingly becomes a father, and a Mother Superior who refuses her any medical relief during an excruciating breech birth (“Pain is her penance,” she declares)—the movie concentrates on bringing together Philomena and Coogan’s snobby Oxford-educated journalist Martin Sixsmith, who’s been booted from his lofty post as an political adviser and reduced to doing human interest stories. Though he would rather be writing a book on Russian history, he offers to help locate Anthony in return for writing an article based on her experiences.

Their personalities initially clash: she is open-hearted, literal and chummy, he is smug, sarcastic and condescending. Often, it’s almost like an Abbott and Costello routine. Whenever Philomena cheerily introduces Martin, she calls him “Martin Sixsmith, News at 10.” He corrects her by saying he worked for the BBC, then follows with a mention that he ran the Moscow bureau and also covered Washington, D.C. If the movie has a failing, it’s that the humor occasionally plays a little too on-the-nose cute, what with Philomena cooing over the bathrobes she found in her hotel room and phoning Martin to see if he needs one, or chatting up Mexican food servers about the joys of nachos.

As it turns out, they are the right kind of good cop/bad cop team to dig up the facts surrounding Anthony’s current whereabouts. They first visit the convent in the Irish countryside, where they are conveniently told that all information on the subject was lost in a fire. Martin then relies on his D.C. contacts to see if they can fill in any blanks. Off they go to Washington, and while the details of what they discover are easily found with a quick Google search, especially since the real-life Sixsmith wrote a book about the outcome, it is best to come to the film with as little background knowledge as possible.

“I’d like to know what he thought of me,” says Philomena, explaining her decision to seek out Anthony so late in life. “I’ve thought about him every day.” Rest assured, she gets her wish.

Both characters develop a profound respect and fondness for each other. Their contrasting reactions to what they uncover allow Frears to condemn the Catholic Church for sanctioning such a cruel racket while upholding the importance of such core religious values as forgiveness and understanding.

After trying to follow such fellow British funnymen as Ricky Gervais and Russell Brand by crossing over to the American public in “Around the World in 80 Days” and “Tropic Thunder,” Coogan might finally break out with his subtle efforts here.

But Dench commands the proceedings, and Frears lets you know it with lingering closeups of her face, each line and wrinkle underscoring her ageless beauty and boundless ability to make us care deeply no matter what role she undertakes. Botox be damned. While His existence is bitterly questioned by Sixsmith during the course of the film, we will adopt Philomena’s stance and say, “God bless Judi Dench.”